Wood Synthetics

The best-recognized synthetics for woody aromas have been around for years. Vetiveryl acetate has a clean vetiver-like intensity and ties together with other older synthetics such as cedryl acetate, cedrol and vetiverol.

In the last 40 years, however, a wide variety of woody synthetics has cropped up. While many of them are “captives” (only available to major perfume houses), I’ve still been able to track down a large number, each with its own nuances.

Arcadi Boix Camps, in his book Perfumery: Techniques in Evolution, describes many of them.

Palisandin, he says as has an odor of cedar and musk, with undertones of ambrette seed. In any case, this aroma chemical is delicate and slow to become perceptible. I hate to admit it, but he perceives more than I do.

Andrane, he describes as having the precious wood component of patchouli. I like to combine it with patchouli itself.

One of the most important innovations of recent years was the discovery of methyl cedryl ketone, or vertofix Coeur. It has a delightful smell of cedar that makes itself present without taking over. ABC goes on about it and emphasizes how well it goes with methyl ionones, irones, ionones (especially allyl ionone), but does state that it lacks vitality. Later, under his description of cedramber, he describes how it can be added to vertofix to liven it up.

I find cedramber to be sweet and balsamic. ABC describes it as being between amber and patchouli and says it goes well with undecylenic aldehyde (C-11), cyclamen aldehyde, lyral, lillial and others. One of cedramber’s attributes is its ability to pull back the sweetness of a perfume that might otherwise be cloying. ABC describes an accord of ciste-labdanum (the absolute and the oil), nutmeg essential oil, pachouli, Vertofix, musk ketone, castoreum absolute, isobutyl quinoline, isoeugenol, glycolierral, benzyl salicylate, centifoyl and vanillin. I haven’t tried it yet.

Natural Musk

The angst of my mother leaving me alone at night with my bullying brothers is forever coupled with the delicious aroma of her 1940s Vol de Nuit. No sooner would she put it on to get ready for an evening out and a tight knot would form in my tummy. When she returned, in the early morning hours, she no longer smelled like Vol de Nuit, but rather like something else, something even more beautiful and soothing, almost like the smell of her skin itself. She stank of natural musk.

Despite what some writers have asserted, natural musk is nothing like synthetic musk. Synthetic musk is usually sweet, sometimes cloyingly so, and never has the deep animal complexity of the natural stuff. In fact, I suspect that most perfumers have never smelled natural musk since it hasn’t been used in perfumes since the 1950s. This suspicion is underlined by the fact that modern musk perfumes don’t smell at all like natural musk.

Natural Musks

I was lucky to enough to procure some musk from a perfumer friend who was getting rid of some old stuff. Even though musk is sold (illegally), the small deer from which it is obtained is endangered so that buying more is out of the question.

When I uncorked the musk—I was instantly brought back over 60 years ago, witnessing my mother’s return from one of her parties.

The musk deer inhabits the Himalayas, from Tibet to Nepal to India. Each region has its own character and, in fact, each deer has its own scent. One in my collection is an authentic white musk derived from gazelles. It smells nothing like brown musk, but has a deeply fresh and satisfying rosy character. The Indian red musk was the one most reminiscent of my mother, completely dry with little sweetness. When I close my eyes, looking for the right descriptor, I see forests and oceans and whole panoramas. The smell is extraordinarily complex and almost impossible to describe. The most expensive musk is called Dhen Musk Ultimate and is the sweetest of them all. I prefer the dryer ones such as a Kashmiri “brown” musk and the Indian “red” musk. The most beautiful to my mind (the best musk supposedly comes from Tibet), is the Napalese Kashturi Ultimate.

Natural musk stays around forever and will scent a room for centuries. It clings to the skin which is partly why it was such a good fixative. Even when the rest of the perfume has completely worn off, musk stays on the skin for many hours.

What is an “Oriental” Perfume?

Opium (the perfume), popular in the 70s and 80s, is an example of a perfume that uses both the ambreine and the mellis accords, with coumarin, a component of both, linking the two.

In perfumery, the word “oriental” denotes a rich, dense and complex perfume. It has nothing to do with whether it is Asian or not. Shalimar is probably the best-known example.

Opium, by Yves Saint Laurent

According to J.S. Jellinek, in Perfumery: Practice and Principles, oriental perfumes can be divided into those such as Obsession and Must de Cartier that are based on the ambreine accord, a mixture of civet, bergamot, patchouli, vanillin, and coumarin, that gives a deep and satisfying softness and gentle sweetness to floral or spicy perfumes, and those based on the “mellis” accord. The mellis accord, upon which Coco, Youth Dew, and Opium are based, includes benzyl (or other) salicylate coupled with eugenol which, of course, smells of cloves. These two compounds form an accord, the same accord used in L’Air du temps, Anais Anais, and Paris. Added to this famous accord are hydroxycitronellal, patchouli and coumarin, with woods and spices, to form the final mellis accord.

In Must de Cartier, we encounter an accord of hedione, sandalwood, and galaxolide that’s used in conjunction with the mellis accord.

Opium (the perfume), popular in the 70s and 80s, is an example of a perfume that uses both the ambreine and the mellis accords, with coumarin, a component of both, linking the two. In Opium, we see a few modern developments including the use of lyral to reinforce the hydroxycitronellal and Vertofix to function as the main woody material. As in Shalimar, Opium contains a good quantity of castoreum to bring out the leather character. Later perfumes such as Coco, placed a greater emphasis on floral notes, and include hedione to reinforce the accords. Sandalwood, once used prodigiously in oriental perfumes, is now rare and expensive. Fortunately, there are a number of synthetics which are nowadays used to emulate the smell of authentic sandalwood.

Perfumery: Practice and Principles, by R.R. Calkin and J.S. Jellinek

My first copy fell apart and I’ve had to order another.

Perfumery: Practice and Principles, by Robert R. Calkin and J. Stephan Jellinek, is my favorite perfume book. First published in German in 1954, it came out in English 40 years later.

My first copy fell apart and I’ve had to order another. Now, this second one is beat up.

Chapter 12, “Selected Great Perfumes,” breaks perfumes into families: Floral Salicylate Perfumes, Floral Aldehydic Perfumes, Floral Sweet Perfumes, Oriental Perfumes, Patchouli Floral Perfumes, Chypres, and A New Style of Perfumery. Each of these sections includes about five perfumes. We see how they’re related and how they’ve descended, one from another.

Perfumery: Practice and Principles

The chapter opens with an analysis of the “floral salicylate” perfumes, starting with the great classic, L’Air du Temps, here described as “one of the most important perfumes ever made.” C and J break the perfume’s aroma into accords, starting with a carnation accord, which forms the heart of the perfume and “dominates the perfume throughout its evaporation.”

The accord contains eugenol (cloves), isoeugenol (stronger cloves), ylang ylang (sweet, tropical flowers), and a trace of vanilla. Benzyl salicylate, a classic floralizer, which doesn’t have a very strong smell of its own, completes the accord.

The base note is comprised of methyl ionone (violets), vetiveryl acetate (like vetiver, but less broad, more focused), sandalwood (a deep, but subtle green woodiness), musk ketone and musk ambrette. Musk ketone is rarely used anymore because it collects in the environment; musk ambrette is forbidden. I’m not sure what musks are used in newer versions, but they give the perfume a different character. The original version would no doubt have been made with natural musk. It must have been unimaginable.

J and C emphasize that the original version contained naturals such as jasmin and rose absolutes, in amounts that would horrify a modern CFO.

Next, we’ll talk about the middle and top of the perfume and how it all comes together.

Exaltation

“Nonalactone” is somewhat ambiguous as there are several, but all are milky, laconic, and a little woody.

On one hand, it seems there is a paucity of exalting compounds. Jellinek, In addition to several aldehydes, considers only two aroma chemicals to be exalting—“nonalactone” and “styrol.” “Nonalactone” is somewhat ambigous as there are several, but all are milky, lactonic and a little woody. Poucher describes styrol: “Styrol (Styrolene) is a fragrant liquid, having an odour slightly recalling that of naphthalene…identified as a constituent of several, natural balsamic exudations, notably storax.”

Jellinek’s list contains only three naturals: alant oil, birch tar oil, and carrot seed oil. The second two are familiar to any perfumer, but the first one, also known as elecampane oil, seems impossible to find. He also lists two “resinoids,” tonka and olibanum (frankincense).

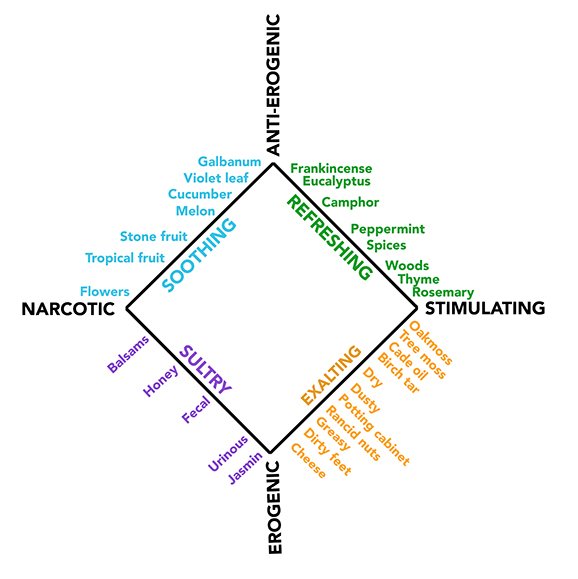

But, the odor effects diagram at right lists 11 compounds or aromas that are exalting, moving from stimulating to the more funky point on the diagram, erogenic. It may be hard to imagine the smell of cheese as being erogenic, but when appropriately disguised, it can have this effect.

Coty’s Chypre de Coty: A Study in Odor Effects Contrasts

Jasmin absolute is perhaps the most important ingredient in all of perfumery, special because it contains intrinsic contrasts that amplify many perfumes and perfume ingredients.

The perfume style referred to as “chypre,” was first embodied in Coty’s Chypre de Coty in 1917. Deconstructing this perfume provides a good illustration of how to use the Odor Effects Diagram, which I’ve included again below.

I’ve never smelled Chypre de Coty—few people have—but deducing from the materials it contains, I would think it would include mossy, citrus, musky, floral, and spicy notes. It would have notes of authentic civet, ambergris, and musk. It would, of course, contain jasmin.

Jasmin absolute is perhaps the most important ingredient in all of perfumery, special because it contains intrinsic contrasts that amplify many perfumes and perfume ingredients.

Jasmine contains jasmone which, to me, is slightly woody with an apricot aspect. In any case, it is considered stimulating. Indole is a strange off-putting aroma found in feces that the plant uses to attract insects. It is highly erogenous.

Jasmone and indole create an exalting tension between the stimulating and the erogenous corners of the diagram.

Jasmine is also sultry because it contains narcotic materials such as methyl anthranilate and benzyl acetate, which form a line to the erogenous indole, natural musk (artificial musks are considered narcotic), and ambergris. These last two are added to augment the erogenic nature of the perfume.

To heighten the stimulant effect, Coty includes oakmoss, which reinforces the exalting quality of the perfume. He also includes spices, vetiver, and patchouli to enhance the stimulating effect of the oakmoss.

Coty also used a large amount of bergamot for Chypre de Coty. It’s an anti-erogenic citrus fruit as it contains terpenes, along with lynalyl acetate and linalool—both narcotic. This creates a line between anti-erogenic and narcotic that produces a soothing effect.

Notice how these two lines that Coty forms—soothing and exalting—are in opposite positions. These complexes, both inherent in the flower, contribute to jasmin’s usefulness as a perfume material.

Coty’s great Chypre de Coty is a supreme example of how opposing odor effects create excitement and tension in most any creation.

Scent Memory: Wine and Perfume

I sometimes recognize Burgundy by a note of what reminds me of Clorox…

I’ve got an old nose. Not in the sense of an “old soul,” but rather of an old shoe. But while it isn’t what it was in the 1970s when I was training it on old Lafite, it’s still there. Perhaps as I get even older, there will be less of it and while this isn’t something I relish, working with wine and perfume is much about memory. Few of us without a sense of smell can compound perfumes in the way Beethoven did the ninth, but those with deep olfactory associations can get by with relatively weak noses.

During my 20s, I had to walk along a hundred-yard weed-strewn stretch of meadow that ran along trolley tracks, to get to the restaurant where I worked. I played a game of labelling as many aromas as I could, even though I knew what nothing was. I just made up some method of remembering each smell. After doing this for several weeks, I had over a hundred aromas I could name.

Of course, much of what I say is supposition, but training our sense of smell is more about the brain than it is the nose. The more we smell, consciously and with intention, areas of the brain that may well have atrophied, stir back to life. When I first started smelling perfume ingredients, there were many I couldn’t detect. I couldn’t smell artificial musks, sandalwood or vetiver. Now not only do I recognize sandalwood, but can usually can tell where it’s from. I don’t think that I necessarily rejuvenated actual olfactory cells, but more likely activated the part of the brain that handles them.

I’ve been with a lot of people when they taste a particular wine or smell a particular perfume for the first time. Often, the first impression is vivid, usually of a memory of a long-forgotten place with no real understanding of how these associations came to be. Everyone first assumes these memories or associations are “wrong” and that these aromas and smells have an objective identity more important than our own impressions.

Just like any art form, every work occurs in a context. Something that looked cool in the 70s, be it fine or decorative art, may now look ridiculous. While I learned quickly to taste and even identify a good number of wines, it took much longer to appreciate these wines in a broader context, with a more pronounced sense of their provenance, the traditions behind them, and the inevitable evolution of styles that characterizes any vital art form.

It is in this area, where my knowledge of perfume is weak. People who’ve grown up with scent, more likely women, will recognize styles from various periods, nuances between brands, or what a particular perfume may imply. My only context, on the other hand, were the smells of my mother’s perfumes, some which dated from her wedding day in 1940. And while memories of these vintage creations remain sharp and evocative, after that, I know nothing.

Richebourg, one of Burgundy’s greatest vineyards

Because of this, my own perfumes are outsider art—they occur outside a traditional fine art context. If I could really use the ingredients popular in my mother’s time, perhaps my memories could serve me well, but given current restrictions, this is impossible.

Rule number one. There is no right answer.

The trick to better understanding wines and perfumes, is to group our impressions and label them in such a way that they make sense to ourselves. Gradually, we will be able to connect these associations to “objective” terms understood by others. For example, a glass of Corton may be reminiscent of berries, mushrooms, truffles, all layered together in a transcendent structure. For practical purposes, this is all we need. But as we gain experience, we begin to clump together our perceptions with ever greater precision. An amateur might identify the Corton as a Burgundy, while those more experienced may narrow it down to ever smaller locales. The berry and mushroom combination may be enough to declare the wine as Burgundy. Other more subtle nuances—a trace of mint or spearmint for example—might signal we’re at the more southern part of the iconic Côte de Nuit. If we have an effective roster of other aromas (and, for wine, flavors and textures) in our heads, we may be able to recognize Corton. If we really know this region, we’re likely to be able to pinpoint the maker.

The training of the nose is more about memory than simply giving your nose a workout. It is the accumulation over time of olfactory memory that allows us to identify nuances and subtle accords. These memories don’t have to sound good. You may identify the old Corton or pick apart the ingredients in your mother’s Quelques Fleurs, by remembering that dirty socks nuance or that strange memory of a place in your childhood. I sometimes recognize Burgundy by a note of what reminds me of Clorox; I can nail down certain vintages by whether they have an elusive dog feces aspect. What you smell doesn’t have to be a “pleasant” association. Half the time truffles remind me of mildew.

Working with Musk

I don’t want to offend everybody, but anything that makes a strong statement is likely to offend at least some.

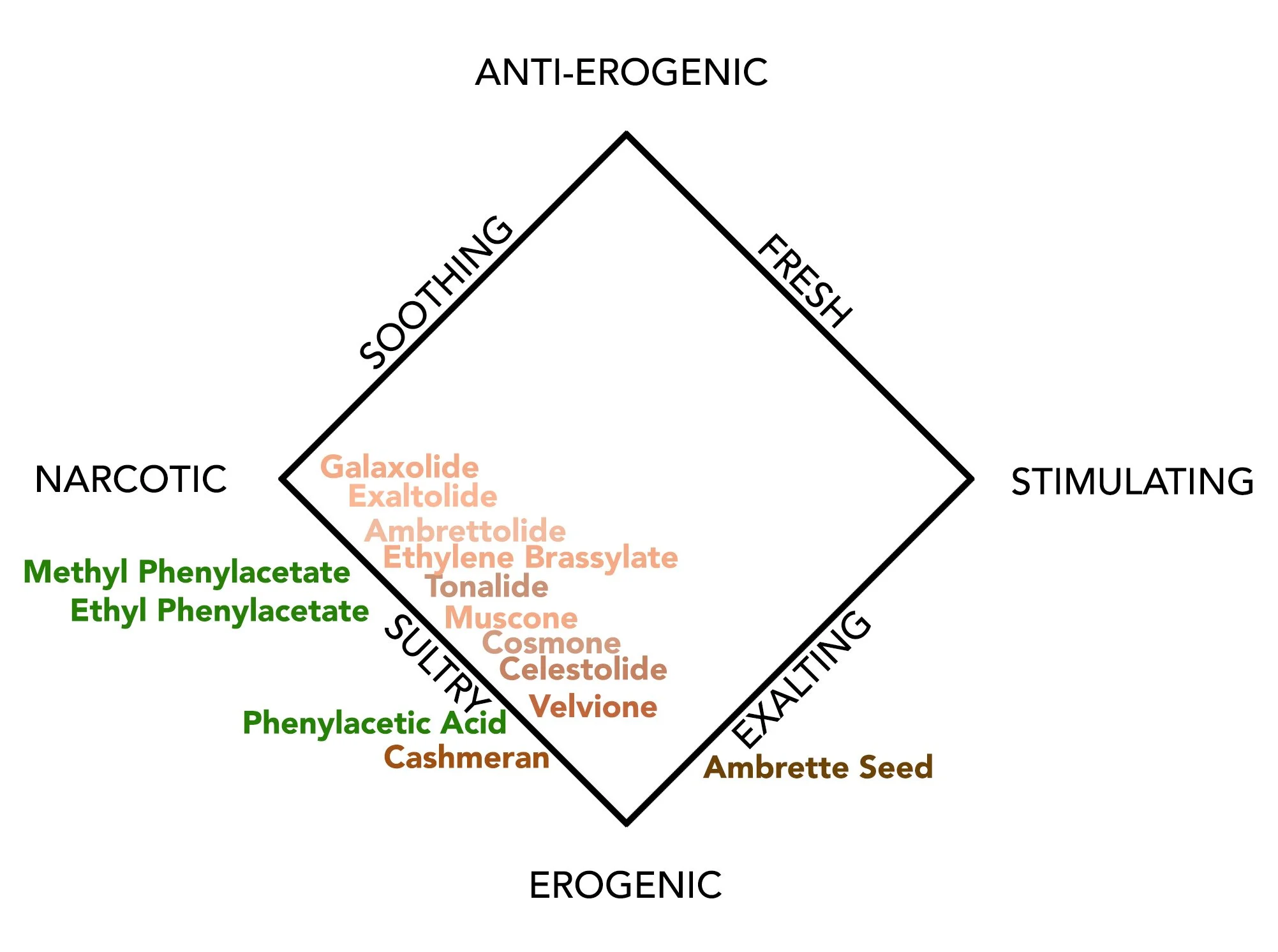

Odor Effects Diagram of Brooklyn Perfume Company’s Musk

There are two main kinds of musk: natural and synthetic. Natural musk comes from a small Himalayan deer which is now endangered. I remember my mother reeking of it, but that was the 1950s. It may be the most delectable smell that exists. In later decades, natural musk was replaced with synthetic musk, sometimes called “white musk.”

Artificial Musks

Unfortunately, synthetic musk never approaches the aroma of deer musk and, in fact, smells so little like it that I suspect many perfumers have never smelled the real thing. In addition, many people are anosmic to artificial musk—they just can’t smell it.

When I put together Musk, I used a large combination of musks so that people who are anosmic would be more likely to smell it. While artificial musks are immediately recognizable as such, I have never smelled two the same in my collection of 30 or so.

Much synthetic musk smells like clean laundry or is so very smooth that, again, it reminds me little of mother’s post-party aroma. Here, again, I suspect that those who make these perfumes have neither experienced deer musk or are afraid of offending the public with crude and, sometimes, fecal odors.

I don’t want to offend everybody, but anything that makes a strong statement is likely to offend at least some. So, I put animalic stuff in the perfume to make it funky and pheromonic. (One friend asked me, bewilderedly, if I were wearing some kind of “attractant.”) The result is something that shimmers between the delicate and the forceful, between clean laundry and animals in heat. It’s not for everyone.

Here, I’ve used Jellinek’s chart as the basis for my own analysis of the perfume and to illustrate how it is structured. It involved a bit of guesswork, since each musk has its own aroma profile and I wasn’t able to find informationmation about the odor effects of a specific musk.

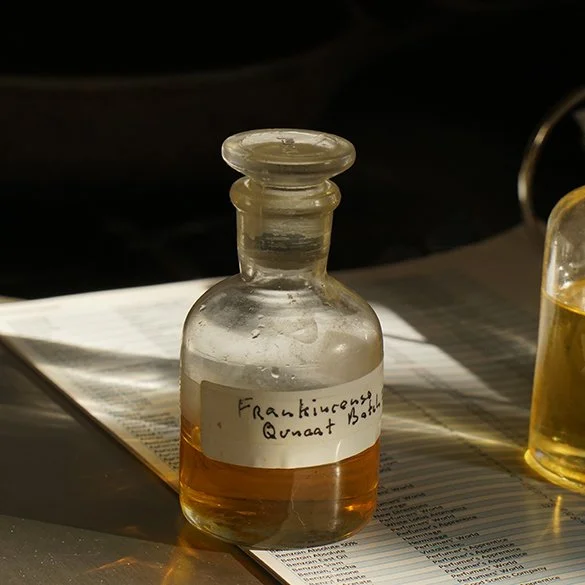

Frankincense

…frankincense…reminds me of lemon furniture polish.

To be frank (no pun intended), I’ve never really liked frankincense since it reminds me of lemon furniture polish.

When I first started my adventures in perfumery, I ordered 17 different frankincense oils from all over the world, including very expensive wild harvested, green Oman, and every exotic and expensive thing I could find. The all disappointed me except one. I had ordered it from Singapore and it was divine, unlike anything I’ve ever smelled. I used it in my original oud.

A year ago, the frankincense from the same supplier came in with the balsamic thing and the lemon polish thing in about equal parts. It’s still the best frankincense out there.

I’ve since ordered more, and it’s pure furniture polish. I’ve asked them about the original and they said they have a little from several years ago. Their minimum order is 5 kilos. That’s an enormous amount for me, but I would do it without hesitation if it’s the old stuff.

This all makes me wonder if the frankincense described in the bible and in other sources that go on about it, isn’t the balsamic oud. The furniture polish thing is perhaps something new?

The new oud contains little frankincense and is a little bit harder and austere than the first and second editions. It also contains new exotic woods to round it out and provide a woody top note. This being said, I believe it to be the best expression of oud of all three editions.

Fooling Around with Jasmin

Mimosa, again, smooths out a composition and rounds out its subtle and complex aroma.

I’ve been playing a new game: I reconstruct flowers, working with a list of essential oils, absolutes, and aroma compounds, that gives no quantities. The challenge is to balance the amounts of these ingredients to come up with a viable replica of the flower at hand. Ideally, you have the real flower next to you to guide you. Second best, use a good absolute to provide a smell comparison. As a basis for my experimentation, I used a list of ingredients, grouped by class, in Perfumery: Practice and Principles by Robert Calkin and Stephan Jellinek.

Benzyl acetate is perhaps the most classic of jasmine aroma chemicals, used in every formula I’ve seen. While its aroma does in fact resemble jasmine, it is coarse and industrial. Other benzyl esters—benzyl proprionate, benzyl valerianate, benzyl isobutyrate and dimethyl benzyl acetate—are used to modify the basic benzyl acetate aroma. Each has its nuances, some fruity, and some a little funky.

The second grouping of compounds is based on phenylethyl alcohol with its distinct rose, but chemical, aroma. Phenylethyl acetate smells a little like wine that has evaporated in the bottom of a glass. Other compounds are phenylethyl butyrate, phenoxyethyl isobutyrate and phenoxyethyl alcohol. When combined with phenylethyl alcohol, these compounds contribute to the rosiness while attenuating the chemical finish of phenylethyl alcohol.

Jasmin Collection

Fool around with the rose compounds until you have a mixture you like and combine this mixture with the jasmine mixture. In the finished perfume, I ended up using equal parts of the benzyl acetate complex and the phenylethyl alcohol mixture, but if you do this at the beginning, the benzyl acetate mixture takes over. I started out with five times the rose mixture to the benzyl acetate mixture to achieve the right balance, but added more of the benzyl acetate mixture as I continued adding other ingredients to the perfume.

After achieving a balance between the jasmine (benzyl acetate) mixture and the rose (phenylethyl alcohol) mixture, it’s time to experiment with muguet (lily of the valley). Three compounds—hydroxycitronellal, lilial, and lyral—are usually used for the lily of the valley aroma. This light and fresh mixture is added to the jasmin/rose mixture in about equal parts muguet, rose, and jasmine mixtures. The mixtures need to be evaluated to get the ratios right.

Geranium, which is very rose like, is often used in floral perfumes. Its chemical backdrop is geraniol which in fact does smell like geranium, but without its richness and irresistibility. I used three parts geraniol to five parts muguet complex.

Eugenol and iso-eugenol are essential to emulate the spicy, slightly clove-like character of jasmine. Be careful, but you may find that the formula calls for a considerable amount.

Floral perfumes invariably contain linalool. Linalool has a unique freshness that most of us have encountered in hand wipes. Linalyl acetate, closely related, is subtler with an almost pine-like aspect. Be careful when using linalool and linalyl acetate; while they smell light, they can easily take over.

Green notes come next and we encounter our first natural, violet leaf absolute. Violet leaf is very green with a distinct aroma of cucumbers. Our author also suggests hexenyl acetate as a green note. It’s not as green as the violet leaf, but lacks the cucumber aspect which, if you’re not careful, can take over.

Many flowers contain cinnamon aspects as well as those of clove. In classic perfumery, the fallback cinnamon compounds are amyl cinnamic aldehyde, hexyl cinnamic aldehyde, and cinnamic alcohol. Amyl and hexyl cinnamic aldehydes are relatively subtle. If I want a distinct cinnamon note, I use cinnamic alcohol.

Aurantiol and methyl anthranilate (both smell like Concord grapes) add a necessary fruitiness.

Indol is one of the most important ingredients in jasmine and certain other flowers. It’s stinky at best, but is essential because it draws flies which the flower depends on for pollination. If you smell the indol alone, you’ll have a hard time imagining it in your perfume, but you may find that your formula requires a fair amount of it to bring the flower aroma into focus.

Jellinek’s next suggestion includes the family of paracresols: paracresol, paracresyl acetate, paracresyl phenylacetate. At first sniff, paracresols smell to me a little bit like creosote, but with an intriguing animal aspect that goes well with florals, especially narcissus. There’s something dark about these smells; they make a composition veer toward a minor key.

Last, Jellinek suggests using naturals to give vitality, freshness, and to smooth out the composition. Ylang and cananga are both on the list. These have very similar aromas, but cananga (which is sometimes used as a cheap substitute for yang), has a slightly vegetative aspect that works in this formula better than ylang. It should be added in very tiny amounts.

I carefully sniffed my composition next to a good jasmine absolute and found that the jasmine had a wild non-floral aspect that reminded me a bit of hay. I added a tiny amount of hay absolute to provide these notes. Immortelle (an absolute of helichrysum) has a distinct aroma of maple and curry with a suave background. It added considerable finesse and smoothness.

My last addition, before reinforcing the jasmine with jasmine absolute and the chemicals with naturals, was mimosa absolute. Mimosa, again, smooths out a composition and rounds out its subtle and complex aroma.

One Approach to a Luxurious Jasmine Perfume

Frankly, I’ve been amazed by the result. The potion really smells like jasmine. It’s not as voluptuous and hasn’t the same deep richness, but it might very well take someone in.

The composition is finished with jasmine absolute to fill in the nooks and crannies that the chemicals and naturals didn’t reach. In commercial perfumes, there’s a trace of jasmine if you’re lucky. Vintage perfumes contained as much as 10% of the absolute. People must have smelled really good back then.

As can be seen on the odor effects diagram, jasmine is unique. It is not only narcotic (typical of florals), but also erogenic because of the smelly indole it contains.

If you’re making a fine perfume, you will want to reinforce chemical aromas with those of naturals: rose for phenylethyl alcohol, rosewood for linalool, geranium in addition to the geraniol, clove with iso-eugenol, and cinnamon in addition to cinnamic alcohol. Be careful with these naturals—they’re very powerful.

One interesting observation. I’ve always heard it said that chemical compositions of flowers and other fragrances last longer than naturals. That’s not the case here. The jasmine absolute lasted much longer on the strip than did the chemical mixture.