My Favorite Books III

The Practice of Modern Perfumery continues its discussion of the odor wheel. As we’ve seen, the lines between each of the points represent sultry, fresh, exalting, or soothing odor effects, while those points that are in opposition--anti-erogenic versus erogenic, and narcotic versus stimulating--create other odor effects. Anti-erogenic aromas suppress erogenic aromas and stimulating elements such as spices, burnt substances, and gourmand materials balance the tendency of the narcotic to intoxicate and put us to sleep when that’s not what we’re supposed to be doing at all. The opposition of the contrasting points introduces tension in the perfume and gives it power.

Mr. Jellenek discusses animal (erogenic) ingredients such as castoreum, civet, musk, and ambergris; and erogenic compounds of plant origin, namely costus root and ambrette seed. Last, there is the aroma chemical, indole. Indole forms part of the smell of certain flowers—jasmine, orange flowers, and acacia are a few. While indole is considered fecal, and has a distinctly dissonant aroma, these flowers wouldn’t be themselves without it. Other aroma chemicals with fecal nuances are phenylacetic acid and its esters (which also smell like honey), phenyl ethyl alcohol (which smells like roses, but has a gentle funky note), and the paracresols (which smell like creosote and tar; they get animal in a perfume).

Now it gets interesting. While these odors are, according to Jellinek, fecal, there are also so-called sweaty notes. These notes are represented primarily by aldehydes, specifically those having from eight to 12 carbon atoms. He goes on to declare that both sweaty and fecal notes must be included together, with the obvious conclusion that any complex containing indole or any other fecal-like aroma, must also contain an aldehyde. This combination occurs frequently in plants, with various proportions of the two elements coming into play.

Now I’m experimenting with using aldehydes with Black Iris. I tried some C-12 MNA, an often-used aldehyde, and found that it focused the perfume and somehow makes it more perfume-like, more sophisticated. Further experiments ensue.

Coming up, Jellenek’s discussion of aldehydes and some important aroma compounds.

My Favorite Books II

While The Practice of Modern Perfumery offers a number of formulas, it’s the incidental stuff I find most exciting.

Author Dr. Paul Jellinek categorizes aromas into four groups:

1 Animal (fatty; waxy; sweaty; putrid)

2 Flowers and balsams

3 Terpenes and camphors (menthol-like; resinous; green)

4 Vegetable materials excluding flowers (roots, seeds, branches, and leaves; characterized as resinous, green, or acidic. Spices are also considered stimulating)

He discusses how each of these groups affects us and arranges them in a diamond showing how they interrelate.

In the classic French tradition, perfumers use aromatic substances from all the main groups, each represented at a point on the diamond. Anti-erogenic compounds, at the top of the chart are known as fresh, minty, piney, or calming like eucalyptus. These compounds are the main ingredients in eaux de cologne. Erogenic compounds, at the bottom of the chart, are funky animal things like ambergris, civet and musk. They are aphrodisiacs and pheremonic. These two contrasting groups are often used together, with the anti-erogenic compounds balancing and disguising the erogenic aromas, which seem disgusting to us if too strong.

Contrasts also occur between narcotic and stimulating compounds. Narcotic ingredients are usually flowers, but various balsams and balsamic compounds also fit this description. These ingredients dull the senses and create a general sense of relaxation. Stimulating compounds include spices, burnt smells, roots (such as orris), seeds (such as angelica), leaves (such as cinnamon), and branches (such as petitgrain).

Between each of these main odor categories are sub-categories with their own odor effects. Honey-like odors, for example, fall between the erogenic and the narcotic. These aromas are characterized as sultry. Fruity smells are both anti-erogenic and narcotic. These are referred to as soothing. Minty odors have both a narcotic and stimulating effect. Smells that we describe as “powdery” (dusty, choking), are between stimulating and erogenic. They are considered exaltants, ingredients that enhance and bring others to the fore.

It’s quite an amazing book and I’m certainly not done writing about it....

My Favorite Books I

Perfumery: Practice and Principles, by Robert R. Calkin and J. Stephan Jellinek, is my favorite perfume book. First published in German in 1954, it came out in English 40 years later.

My first copy fell apart and I’ve had to order another.

Chapter 12, “Selected Great Perfumes,” breaks perfumes into families: Floral Salicylate Perfumes, Floral Aldehydic Perfumes, Floral Sweet Perfumes, Oriental Perfumes, Patchouli Floral Perfumes, Chypres, and A New Style of Perfumery. Each of these sections includes about five perfumes. We see how they’re related and how they’ve descended, one from another.

The chapter opens with an analysis of the “floral salicylate” perfumes, starting with the great classic, L’Air du Temps, here described as “one of the most important perfumes ever made.” C and J break the perfume’s aroma into accords, starting with a carnation accord, which forms the heart of the perfume and “dominates the perfume throughout its evaporation.”

The accord contains eugenol (cloves), isoeugenol (stronger cloves), ylang ylang (sweet, tropical flowers), and a trace of vanilla. Benzyl salicylate, a classic floralizer, which doesn’t have a very strong smell of its own, completes the accord.

The base note is comprised of methyl ionone (violets), vetiveryl acetate (like vetiver, but less broad, more focused), sandalwood (a deep, but subtle green woodiness), musk ketone and musk ambrette. Musk ketone is rarely used anymore because it collects in the environment; musk ambrette is forbidden. I’m not sure what musks are used in newer versions, but they give the perfume a different character. The original version would no doubt have been made with natural musk. It must have been unimaginable.

J and C emphasize that the original version contained naturals such as jasmin and rose absolutes, in amounts that would horrify a modern CFO.

Next, we’ll talk about the middle and top of the perfume and how it all comes together.

Patchouli

Not all of my readers remember the days when patchouli was almost ubiquitous among young people. It was impossible to go to a rock concert without being overwhelmed by thick, dense wafts of the stuff.

Long after, I now know that patchouli is a common ingredient in perfumes. In fact, there is a whole family of perfumes based on it. In my favorite book, Perfumery: Practice and Principles, the authors—Jellinek and Calkin—examine the importance of patchouli in certain formulas and, in particular, how it forms an important accord with hedione.

Five patchouli-based perfumes are explained, and their ingredients elucidated (without the quantities) so I have something to go on in my experimentation. Famous scents like Diorella, Aromatics Elixir, Coriander, Knowing, and Paloma Picasso all revolve around certain common accords based on patchouli.

I went online to my source and bought a small vial of Diorella to guide me (I’m terribly ignorant about what classic perfumes smell like). Using my little vial of Diorella and my book’s guidance, I set out to make my first accord: a combination of patchouli and hedione.

I started out with a 3:5 ratio of patchouli to hedione to form what seemed like a unique accord. Building on this, I added some of my jasmin complex (which contains 10% naturals) to give the accord floral complexity.

It seems that all in this family contain rose so I dutifully added a few drops of rose absolute, which rounded out and gave life to the accord.

Helional is used in most modern interpretations of this family. For those who aren’t familiar with it, it has a distinct marine quality, almost as though it smells like water. Here, Jellinek describes it as (in conjunction with eugenol) “carrying the essential character into the heart of the perfume…”

Next, more work on the heart notes and construction of the top notes.

Eau Fraîche

Eau fraîche, French for “fresh water”, is a type of body fragrance that is sheer and light. If you want a scent that is just for you, as if just coming out from the shower, eau fraîche is it. Eau fraîche is the top choice for those people who prefer delicate and gentle scents. Since eau fraîche is light in nature, it doesn’t last as long on the skin as a perfume does. Eaux fraîche are popular with those who don’t need a perfume to last into the night.

Body fragrance types differ from each other based on the perfume oils these contain. A true perfume contains 22-30% perfume oil. Eau de Parfum is composed of 15 to 20% perfume oil, eau de toilette has 5-8%, and eau de cologne has 3-5%. Eau fraîche contains the least amount of perfume oil at 1-3%.

Eaux fraîche from Brooklyn Perfume Company freshen the air and the surrounding environment. The aromas are pure and natural and will instantly fill a room. Why live with synthetic air fresheners that smell like those little Christmas trees hanging from the rear-view mirror in taxi cabs? The aromas of eaux fraîche subtly scent a room, never fail to please with their garden-fresh smells, chemical-free and purely natural.

Because of their fresh and light smell, eaux fraîche are more suitable during the hot, summer days. Eaux fraîche can also be a lot of fun because they can be layered. In this way you can come up with original scents and change your scent depending on your mood. These sparkling scents will immediately pick up your spirit and provide you with energy and vitality. They range in aroma from deeply floral (Neroli), to an herb-scented martini (Galbanum), to deep green (Violet Leaf) and to fresh grass (Vetiver).

Brooklyn Perfume Company’s eaux fraîche are different than most others because they lack aroma chemicals. The only ingredient is the single natural named on the bottle. For example, Vetiver contains vetiver and alcohol, a trace of preservative, and that’s it. They come in 60ml bottles and in four aromas: Neroli, Vetiver, Galbanum, and Violet Leaf. Neroli has a citrusy and zesty scent as it is extracted from the blossoms of bitter oranges, with hints of honey and spice. Vetiver has an earthy and loam scent, evocative of the smell of freshly cut grass on a sunny day. Galbanum eau fraîche has a green and woody scent, reminiscent of being in the middle of a garden full of plants or in the midst of a forest. Violet Leaf also has a green scent, with hints of cut grass, cucumber, and herbs with a bit of floral aroma.

Sandalwood II

Because sandalwood has gotten very expensive–the best genuine Mysore stuff goes for around $25/milliliter—many try to emulate its scent using inexpensive aroma chemicals. Despite my own efforts, I’ve never been able to match the silvery, creamy woodiness of sandalwood without putting any sandalwood in the mixture.

I’ve since made a couple of discoveries that have made my fake sandalwood almost match the real deal.

I first constructed a wood/sandalwood base using Javanol, Sandela, Vertofix Coeur, cedar Atlas, Iso e Super and guaiac wood to create a woody base. I added amyris (sometimes called “West Indian Sandalwood”) which, in fact, provided a few particular notes that I couldn’t find in any other substance. I included Firsantol, an excellent sandalwood chemical, and dihydro ionone beta, which pulls together the woods. To provide the lactonic creaminess, I added a trace of methyl laitone and bicyclononalactone. Musks, especially Cashmeran, fleshed out the whole construction.

At this point, I have a nice woody complex that one might say is analogous to sandalwood, but not the real deal. To really get the aroma right, I’m going to have to add beta santalol, derived from sandalwood, which is almost as expensive as sandalwood itself. The thing about the santalol, though, is that it’s strong and projects a powerful sandalwood aroma so I could get by using just a little. Last, I added a trace of Laotian oud. This oud is more expensive than sandalwood, but because it works in trace amounts, it doesn’t cost that much to use. It provides a powerful radiant note—be careful or your sandalwood will smell like oud—that ties the whole thing together.

My concoction isn’t as good as Mysore sandalwood, but when used in a perfume, sometimes in conjunction with additional sandalwood, it provides many sandalwood notes, deeply reminiscent of the real thing.

Cedar

As a child, I used to press my nose against the inside of my grandmother’s cedar-lined chest. It smelled of the Orient, as we called it then, of ships and harbors and of China.

Despite having since survived the assault of cheap “cedar-scented” cleaning products, my memory of that beautiful Chinese chest remains intact.

Various Cedar Oils and Cedar Absolute

Maybe because it’s relatively inexpensive, cedar is less often discussed than, say, sandalwood. In addition to lending aromatic support to woods, herbs and florals, cedar oils make excellent fixatives. While more often distilled into an essential oil, cedar may also be extracted with hexane (essentially, gasoline). The hexane is then evaporated off, leaving behind a “concrete,” which is then extracted with ethanol. The ethanol is boiled off in a vacuum, leaving behind the absolute. The essential oil, deeply reminiscent of the wood, is much different than the black and sticky absolute, the pine- and candy-like notes of which are cloyingly sweet to some, delicious to others. When used with discretion, cedar absolute is great for fleshing out delicate florals.

I dug out my collection of cedar oils and absolutes and discovered cedar leaf oil which is also called thuja. This confuses me because I also have a bottle of cedar essential oil from China, that is subtitled “Thuja.” Steffen Arctander, the go-to authority on perfumery ingredients, describes cedar essential oil as blending well with other pine or fir oils as well as citrus, lavender and rosemary. It is used in classic fougère perfumes which contain lavender. To me, it smells stronger and less woody than other oils in my collection. It has a juniper note and a not-unpleasant volatile solvent quality.

In addition to the cedar leaf, my collection includes white cedar absolute, which is like rich and sweet confectionary. Virginia cedar smells like pencil sharpener. Texas cedar is similar, but also has a kind of boozy aroma as though someone had doused it in whiskey. Western red cedar is deep and complexly woody. It’s drier than the others. My thirty-year old cedar Atlas has a bright refined smell that reminds me of sandalwood. It doesn’t smell like sandalwood, but it has some of that same smoothness. Arctander suggests associating cedar oil and absolute with boronia absolute (good luck), as well as labdanum products and “woody-floral” aromas.

Violets

No doubt because of the intense labor needed to accumulate enough violet flowers, violet flower absolute disappeared from the market many years ago. Perfumers use violet leaf absolute instead. While violet leaf has a nice green aspect that fits well with the flower, it doesn’t smell like the flower itself.

Because of their rarity and expense, violet perfumes were chic and desirable in the 19th century, but when ionones were discovered in the first part of the 20th century, the scent of violet was no longer rare. For a while, violet perfumes were all the rage and by the 1950s, violet began to seem old fashioned.

Now that it’s been long enough that none of us remembers their overuse, the time may be ripe for a violet perfume.

The best starting point is alpha ionone combined with methyl ionone and a little dihydroionone beta which has a woody aspect. I made an accord inspired by an article I found on basenotes.net, that describes a violet made with alpha ionone and methyl ionone, with violet leaf absolute, anisaldehyde, irone alpha, heliotropin, orris, bergamot, cassia and leaf alcohol. The accord is good, but it didn’t get exciting until I started to modify it with some of the suggested ingredients in the article. I made 10 test tubes, each with the synthetic violet base, and added lavender, orris, costausol (the original calls for costus, now forbidden by IFRA), opoponax, vanilla, tonka bean, rose, ylang, sandalwood, and boronia, one for each test tube. Each compound gave a twist without obscuring the original accord. Orris works wonders (of course, it’s expensive), as does costausol, ylang, and, most of all, boronia, which has an irresistible mildewy floral quality. Unfortunately, the stuff is super dear so that it’s only practical to use a trace. Sandalwood provides a beautiful dry down, but doesn’t contribute to the floral aspects. I’m still looking for something more violet. Perhaps I’ll try some cedar.

Chypre

Compounds for Composing a Chypre Perfume

Pronounced SHEEPra, the word refers to the island of Cypress, known for its oakmoss, but Cypress has little to do with the evolution of the modern chypre. Instead, the classic chypre style was introduced in 1917 by Francois Coty who created a perfume by that name based on oakmoss, jasmine, and bergamot with musk, civet, patchouli and woody notes. He also used isobutyl quinoline, a compound that has a peculiar odor that some say reminds them of leather. I find the odor off-putting except when it’s added to rich and powerful mixtures to which it adds a definite complexity.

Tragedy befell this beautiful genre several years ago when IFRA (International Fragrance Association) prohibited oakmoss except in derisory amounts. If any component is essential to the chypre’s identity, it is oakmoss with its irreplaceable fragrance of forest floor. True, there are substitutes. Evernyl, to which I add a hint of celery seed, gets us halfway there and de-potentized oakmoss, which has a lot of, but not all, the aroma of the original.

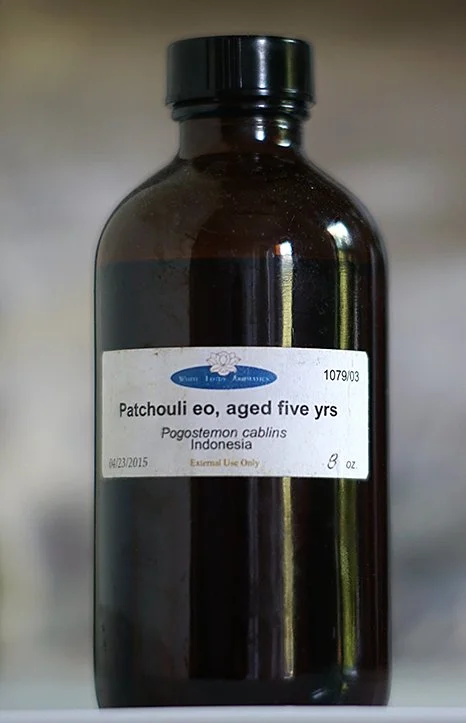

Sometimes when I’m up against a lot of restrictions, I’ll make the original so I know what I’m aiming for. I then gradually take out the offending materials and replace them with viable substitutes. I decided to make a classic chypre with all the forbidden ingredients. I broke out my best oakmoss, Nepalese musk, Ethiopian civet, and 16-year old patchouli. After some tinkering, I made something quite beautiful—it’s hard to miss with ingredients like these—and reminiscent of my mother’s perfumes from the 40s and 50s. (She used to brag about having perfumes from her wedding day in 1940.) Now I need to see what I can take out without damaging the effect. Obviously, natural musk and civet are going to be missed, but it may be possible to come up with something viable without them.

After Shave

Many of us, especially men, who have little experience with perfume, are likely to have encountered eau de cologne, often called “after shave.” Until recently, my own experience of after shave was limited to the cloying vanilla aroma of Old Spice. My brother, as he was getting ready for a date, said to me when I was about 12, “This stuff draws girls like flies!” While its aphrodisiacal abilities are up for question, it was what men wore in the 1960s.

Old Spice Cologne

Unlike Old Spice, which is far from refreshing, most eaux de cologne are used in a different way than perfume and are meant as a refreshing encounter with some persistence, but not the persistence expected of perfume. Some use it, with little or no success, to cover up body odors. It is sprayed more generously than eau de parfum.

Whereas eau de parfum is diluted to 15% to 20% concentration, an eau de cologne may contain as little as 2% of pure aromatic material.

I want to reproduce eau de cologne as it was made in the 1920s. In those days, the very best eaux de cologne were not only distilled, but were aged for a year before being released. The distillation scares me because it involves alcohol which, of course, is flammable. I may distill the concentrate with some, but not all, of the alcohol and then do the final dilution with alcohol shortly before bottling.

After studying contemporary ingredients, it’s amazing to look at recipes from the 1920s. The ingredients for eaux de cologne are virtually all naturals and they include ambergris! So, when I make the stuff, it won’t be cheap, not unless it can be diluted a lot while still retaining its character.

My first attempt is based on lots of bergamot and clary sage. Clary sage acts as a fixative and, being a natural source of linalool, provides a refreshing aspect. Plenty of other citrus—blood orange, lemon, cedrat, neroli, petitgrain citronnier—enter into it as do green ingredients such as angelica seed. I’ve included benzyl isoeugenol which doesn’t have a whole lot of aroma, but acts as a powerful fixative. At this point, the mixture was beautiful, but very green and austere. To sweeten it, I added a small amount of fir balsam absolute. Sandalwood is included, along with koavone and rosewood, to provide woody aspects. I included methyl ionone. Then I let it rest.

I often find, when I’m working on a mixture, that I’ll start to smell what it needs. When I left the room, I realized it needed lavender. I was trying to avoid lavender (such a cliché), but found that lavender absolute rather than the usual essential oil, lent the concoction the floral softness I was looking for.

The next step is to make a 100% mixture of the concentrates and let it age.